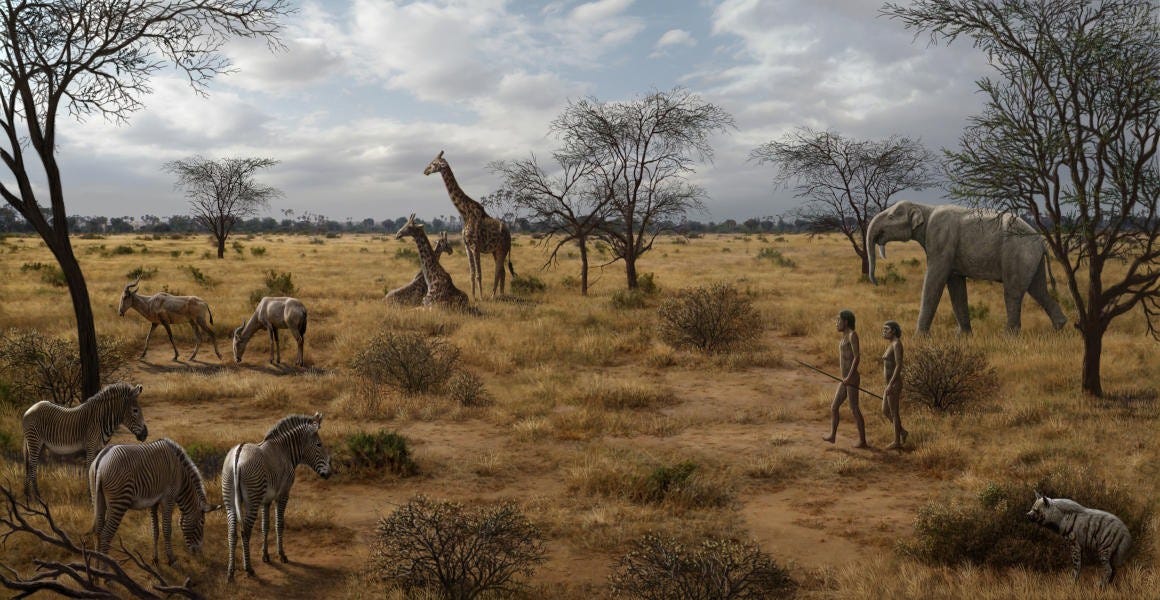

For the first 90% of our 25 million year human evolution, we ate pretty much like the other primates did, about 95% plants which was mostly fruit. Some early hominins, such as Paranthopus bosei (from about 1.7 million years ago), even lived for an extended period of time eating mostly grass, which stimulated the evolution of flat, grinding teeth. Our ancestors became hunter gatherers about 2.5 million years ago. Did this turn them into ‘carnivores’?

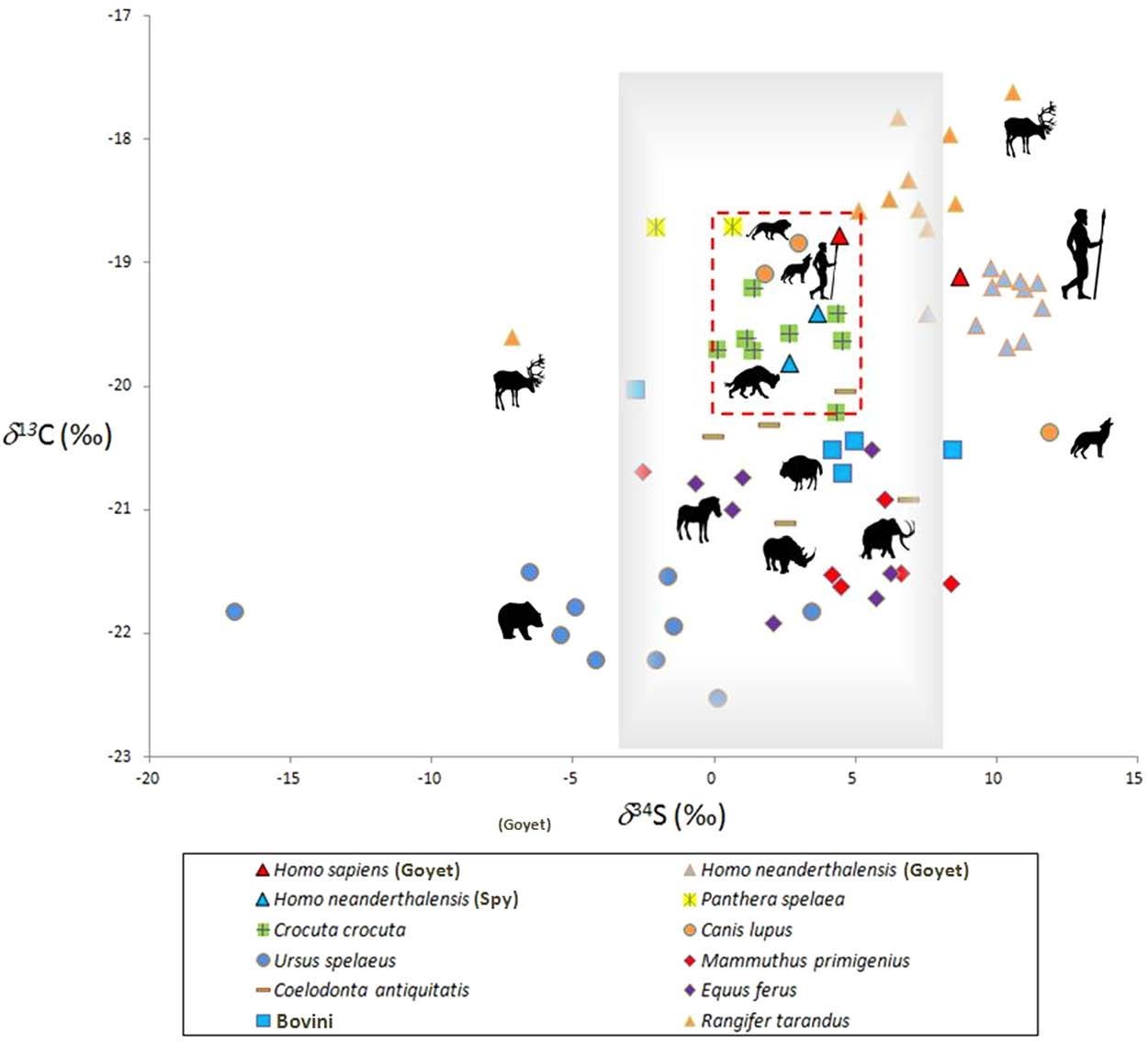

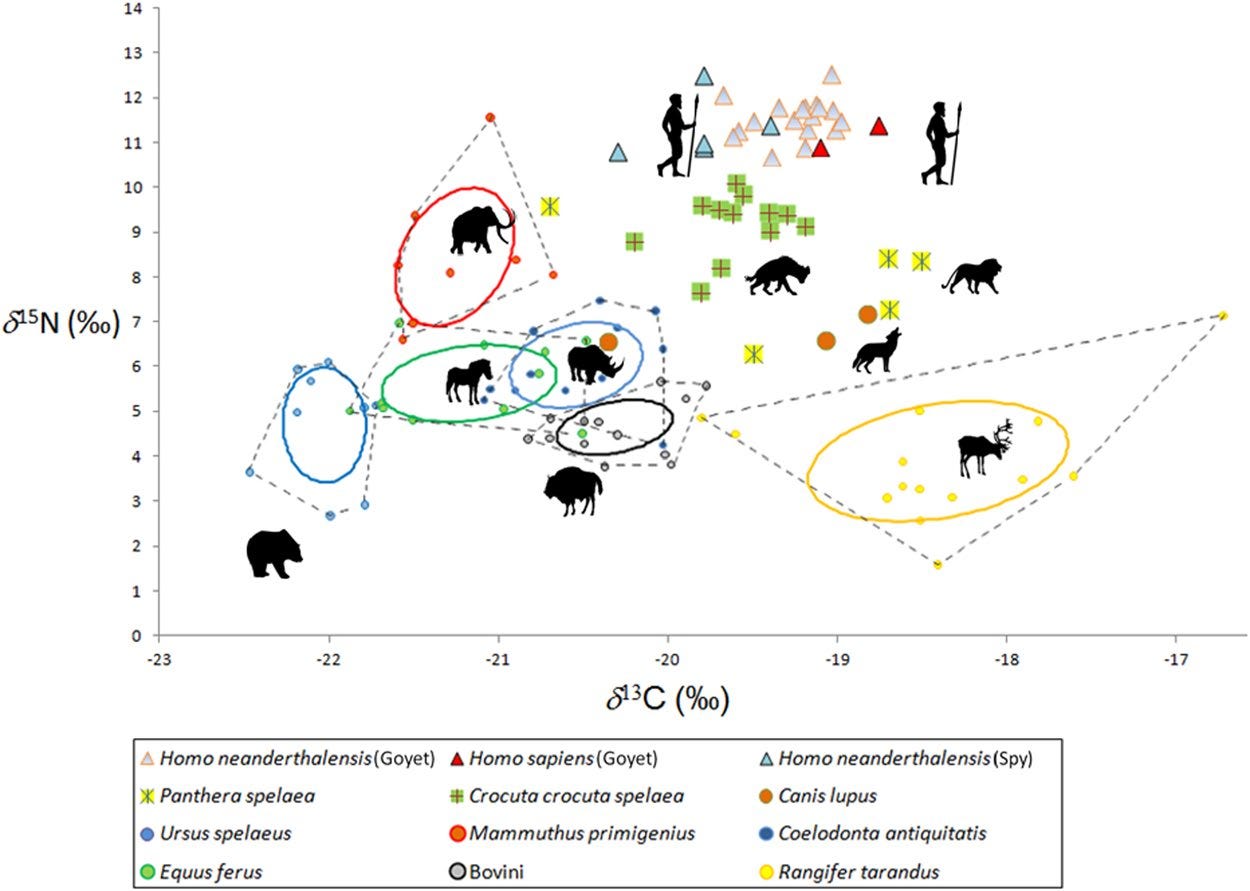

This paper using stable isotopes for carbon, sulphur and nitrogen claims to show speculative evidence that they did. The paper looks at two Early Modern Human (Homo Sapiens) individuals found in Goyet and dated to about 45-40 thousand years ago and compared them to herbivores and carnivores. The further right and higher up on the graph: the higher the position in the food chain.

Not sure what the reindeer is doing above the human in the graph below. I don’t think reindeers ate humans but I could be wrong?

The modern human strolling away from his or her two red triangles would also have eaten fish and high protein sources like nuts, which are not included in the analysis.

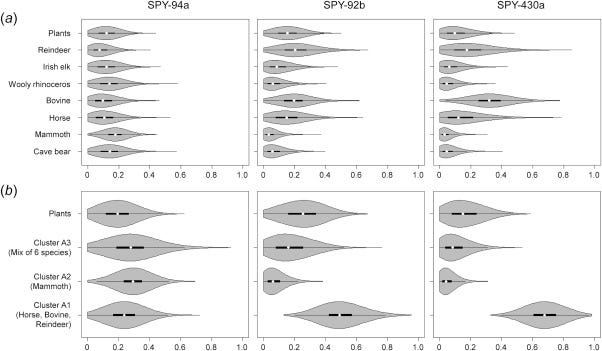

Below: Box plots of the relative contributions (in %) of different prey species to the meat protein portion of the diet of the Upper Pleistocene Modern Humans from Goyet.

The authors estimated that mammoths and reindeer each made up about 25% of the terrestrial meat protein intake. Does that mean that early humans were ‘carnivores’ like wolves?

No.The bulk collagen fraction analysis used above significantly underestimates plant protein sources. This paper shows evidence of a considerable amount of plant protein in the collagen fraction (about 20%) in 3 Neanderthal individuals using a more sensitive method.

Below: Dietary contribution prey animals and plants a) by species or b) by clusters to the Spy Neanderthals, estimated by the SIAR mixing model based on δ15NGlu and δ15NPhe values.

The authors conclude ‘‘the lack of a protein source other than meat in the Neanderthal diet may be due to methodological difficulties in defining the isotopic composition of plants. Based on the nitrogen isotopic composition of glutamic acid and phenylalanine in collagen for Neanderthals from Spy Cave, we show that i) there was an inter-individual dietary heterogeneity even within one archaeological site that has not been evident in bulk collagen isotopic compositions, ii) they occupied an ecological niche different from those of hyenas, and iii) they could rely on plants for up to 20% of their protein source.”

Paleopoop (fossilised faeces) also shows that hunter gatherers consumed 70-150 grams of fibre per day (wild plants have about 4 times more fibre than commercial ones). Early human faeces, filled with fibre and brown coloured from billions of symbiotic plant loving bacteria, would have looked more like horse manure than these white, rock hard hyena nuggets.

Another paper looking at ‘trophic levels’ of European Neanderthals mistakenly calls them ‘top carnivores’. However, the authors themselves admit ‘Isotopic analysis provides information about the sources of dietary protein over a number of years, even though it does not measure the caloric contributions of different foods. As the method only measures protein intake, many low-protein foods that may have been important to the diet (i.e high caloric foods like honey, underground storage organs and essential mineral and vitamin rich plant foods) are simply invisible to this method.’

Isotope analysis of ‘trophic level’ looks at collagen and measures ration of dietary nitrogen compared to nitrogen obtained from the atmosphere. Isotopes vary with climate and age, therefore like must be compared with like. Plants generally have 0-0.2% nitrogen coming from the soil. In herbivores levels of radioactive nitrogen are about 0.3-0.7% and in carnivores about 0.6-1.2%, with omnivores claimed to be in between, although the range already overlaps. These numbers are said to indicate ‘trophic levels’ or place in the food chain with a jump of 0.3-0.5% said to indicate one ‘trophic level’, from herbivore-like to carnivore-like.

High nitrogen levels also indicates the consumption of fish or seafood. Seals, who are at the end of a longer food chain, have levels around 1.8%. The analysis did not differentiate between sources of protein, plant or animals, it merely places in a ‘trophic’ category based on the percentages. A few of the chosen samples (there were only 13 available Neanderthals) had similar profiles, of about 1-1.2%, to the even fewer carnivore (such as hyenas) bones close to the same site and date. The analysis only looks at similarity of protein source which is estimated to be about 25-30% of total calories.

The values for the 10 early modern human bones found could not be included in the ‘trophic level’ analysis because there were no contemporary herbivore or carnivore specimens to compare them with. However, there’s evidence from archeological sites, from 17,000 to 5000 years ago, of considerable consumption of hazelnuts and tubers. This may also explain the more varied analysis and higher nitrogen values of Early Modern Humans compared to Neanderthals.

The study does not show that the make up of the diet of Neanderthals was the same as that of the carnivores. Being at a new ‘trophic level’ by starting to eat some herbivores doesn’t turn you into a carnivore by suddenly changing 22.5 million years of living on mostly fruit. These humans were still perfectly capable of digesting and assimilating wild plants, fruits and tubers.

The carnivore crew spit on epidemiological evidence (unless they appear to exonerate saturated fat) saying that studies are not placebo controlled (hard to do when people know what they’re eating). However, they are happy to be guided in their choices by a complete misrepresentation of a capricious technique analysing bones from a few Neanderthal specimens from thousands of years ago which shows that they ate 60% plants. Besides, Homo Sapiens are not the same species as Neanderthals, and though many Europeans contain a small amount of their DNA, we are not directly related to them nor descended from them.

The isotope evidence only shows that Neanderthals ate some terrestrial herbivores, marine animals; or it could have been other humans! There is evidence, from fracture marks on bones, that they not only ate meat- but also each other. If ‘caveman’ is supposed to indicate biological or genetic determinism of the optimal human diet, then let’s hope that carnivore dieters are not going to start advocating for cannibalism.

The consequences of the ‘caveman’ image by Kapka, as dictated by Marcellin Boule, in 1909 cannot be underestimated. It has caused a persistent misconception of Neanderthals as brutish, savage and primitive.

The days when men were men and women knew their place.

Here is more accurate representation of a Neanderthal woman.

What do we conclude? Neanderthals obtained about 80% of their protein from terrestrial or marine animals (or humans). There would have been seasonal variation in fat content of the animals, however, relative to modern domesticated farmed animals, they have been considerably lower in fat. The true paleo is estimated to be about 20-35% fat, compared to the whopping 50% fat of the new paleo diets. We conclude that the Neanderthals had about 40% of their total calories from animals (about 20% of total calories from animal protein and about 20% of total calories from animal fat) and 60% from plants. And (from studies on paleo poop) about 100 grams of fibre a day, so, nothing like a hyena ‘carnivore’ diet at all.

Was our human physiology affected by becoming hunter gatherers 2.5 million years ago? Let’s look at cholesterol, the length of our intestines and the ability to make vitamin C.

Firstly cholesterol. For the majority of our 25 million year evolution are ancestors were mostly fruit eaters and therefore consumed very little cholesterol. Cholesterol is essential for the body. Not only was cholesterol absent from their diet it was also flushed out by the large quantities of fibre they consumed. For most of evolution we had physiologies that held on tightly to cholesterol. This is now maladaptive, leading to atherosclerosis. Actual carnivores have not adapted this way. For example, a dog, evolved from a wolf, can eat a large amount of fat and cholesterol while not developing the atherosclerosis that a human or rabbit would develop from eating a tiny fraction of the amount. In the Pleistocene, 2.5 million years ago, hunter gatherers began to eat some meat. It’s estimated that early humans consumed about 500mg of cholesterol per day, compared to the whopping 1,300mg of cholesterol in the new paleo diet. Why didn't we evolve to allow cholesterol to pass through the body, like other ‘carnivores'? The evidence from wear and tear on teeth and bones suggests that the average life span of early humans is about 25 years old. This is not old enough, even if they lived to old age of about 45, to develop atherosclerosis and die from a heart attack. An adaptation to high amounts of cholesterol in the diet was therefore not selected for.

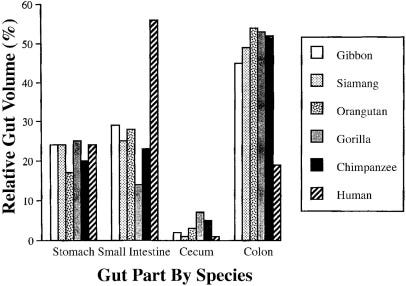

What about our colons? Actual carnivores have evolved short colons to expel toxins from rotting flesh as quickly as possible. Humans have not. The human’s large intestine is about 6 feet long and the carnivore harbour seal’s, which is of a similar body mass, is about 2 feet. This explains why contemporary longer lived, plant based human populations have so little colon cancer and animal based ones have so much. The human gut seems to be optimised to fibre-loving, anti-inflammatory bacteria such Prevotella species which feed colonocytes butyrate (their preferred energy source) and protect the integrity of the gut wall.

What about relative small and large intestine length?

The relative size of the small intestine, even longer than in herbivores, does not indicate that humans became carnivores. Carnivores have larger stomachs and ten times the amount of acid than humans have, to digest raw meat. It is not known when modern humans diverged from great ape relatives in the change in small to large intestine ratio. It may have occurred with the beginning of cooking, which effectively starts the digestion process. Modern humans still ate mostly plants but were not chowing down on bamboo, but eating nutrient dense foods such as nuts and cooked beans, starchy vegetables and tubers. Less time digesting, more time for thinking. Their large intestines were still long enough (only shorter relative to their small intestines) to be adapted for eating lots of leafy fibre, protected by fibre-loving bacteria but also able to absorb cholesterol and toxic bile acids.

And finally vitamin C. In common with great apes, guinea pigs, fruit bats, and some rabbits, humans are unable to make vitamin C, an important antioxidant. Fossilised faeces shows us that not only were humans eating 10 times the amount of fibre than today, they also had 10 times the amount of vitamin C in their diets. Wild plants have considerably more vitamin C than commercial ones. Along with hanging onto cholesterol and keeping a relative long colon, humans couldn’t make vitamin C, because they were consuming so much of it and didn’t need to.

What about hunting animals making our ancestors more clever? There is no evidence that eating more dead animals led to us, about 2 million years ago, to have bigger brains. Big brains are thought to have developed either through ‘better’ nutrition, or because of a need to use the intellect more. However, early humans would already have known the properties and locations of hundreds, if not thousands of plants, and been able to communicate about them to each other. They were already capable of working together to hunt.

What about from ‘better’ nutrition? From PNAS: ‘Many quintessential human traits (e.g., larger brains) first appear in Homo erectus. The evolution of these traits is commonly linked to a major dietary shift involving increased consumption of animal tissues. Early archaeological sites preserving evidence of carnivory predate the appearance of H. erectus, but larger, well-preserved sites only appear after the arrival of H. erectus.

‘Our analysis shows no sustained increase in the relative amount of evidence for carnivory after the appearance of H. erectus, calling into question the primacy of carnivory in shaping its evolutionary history. Our observations undercut evolutionary narratives linking anatomical and behavioral traits to increased meat consumption in H. erectus, suggesting that other factors are likely responsible for the appearance of its human-like traits.’

Maybe the cooking of easily gathered starchy vegetables allowed less time and energy to be spent hunting, chewing and digesting. Perhaps cooking was what enabled human guts to get slightly smaller and brains to get bigger? Sugar, not ketones from a high protein diet, is the brain’s preferred energy source by far.

Encephalisation began about 2 million years ago. It occurred, not just in Neanderthals and early humans, but also in mainly grass eating hominims such as Paranthopus. Encephalisation does not necessarily indicate the evolution of intelligence. Homo floresiensis, who lived 95,000 to 50,000 years ago, had smaller skull capacity (360cc) compared to Homo naledi (460-610cc) who lived earlier, around 300,000 years ago in South Africa. Nicknamed the hobbit for its 1m height, Floresiensis made stone tools and had many other characteristics of Homo sapiens. It’s not the size that counts: it’s what you do with it.

So what kind of diet do contemporary long lived, healthy populations have? You guessed it, rural Africans and Chinese eating mostly plant based, in some cases 70% centred on sweet potatoes, have 17 times lower CVD as well as lower hypotension, diabetes, stroke, gallstones, hernia, hemorrhoids, cataracts, macular degeneration, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and lower colon, prostate and breast cancer risk. And when put to the test a whole food plant based diet can reverse heart disease, the only diet shown to do so.

The new carnivore diet is nothing like the carnivore-like diet of early humans, which itself was nothing like an actual carnivore diet.

In 2020 humans slaughtered 73 billion cows, chickens, pigs, and sheep for food and of the 11 billion animals in the US slaughtered each year 95% of them had spent their short, miserable lives on factory-farms. Although carnivore eaters encourage free-range, these expensive products are only available to, the mostly white minority, who can afford them. ‘Grass-fed’ animals emit even more methane than factory farmed, they are not carbon neutral let alone carbon negative, that’s a lie. There would not be enough land for ‘grass-fed’ animal products for 8 billion people even if every First Nation, wild horse and tree in the world were finally finished off.

To consume the true early human diet of low fat, unprocessed food, to cause considerably less damage and be protected from insulin spikes, atherosclerosis, colon cancer and early death; contemporary humans may wish to think about a whole food plant based diet.

🐒