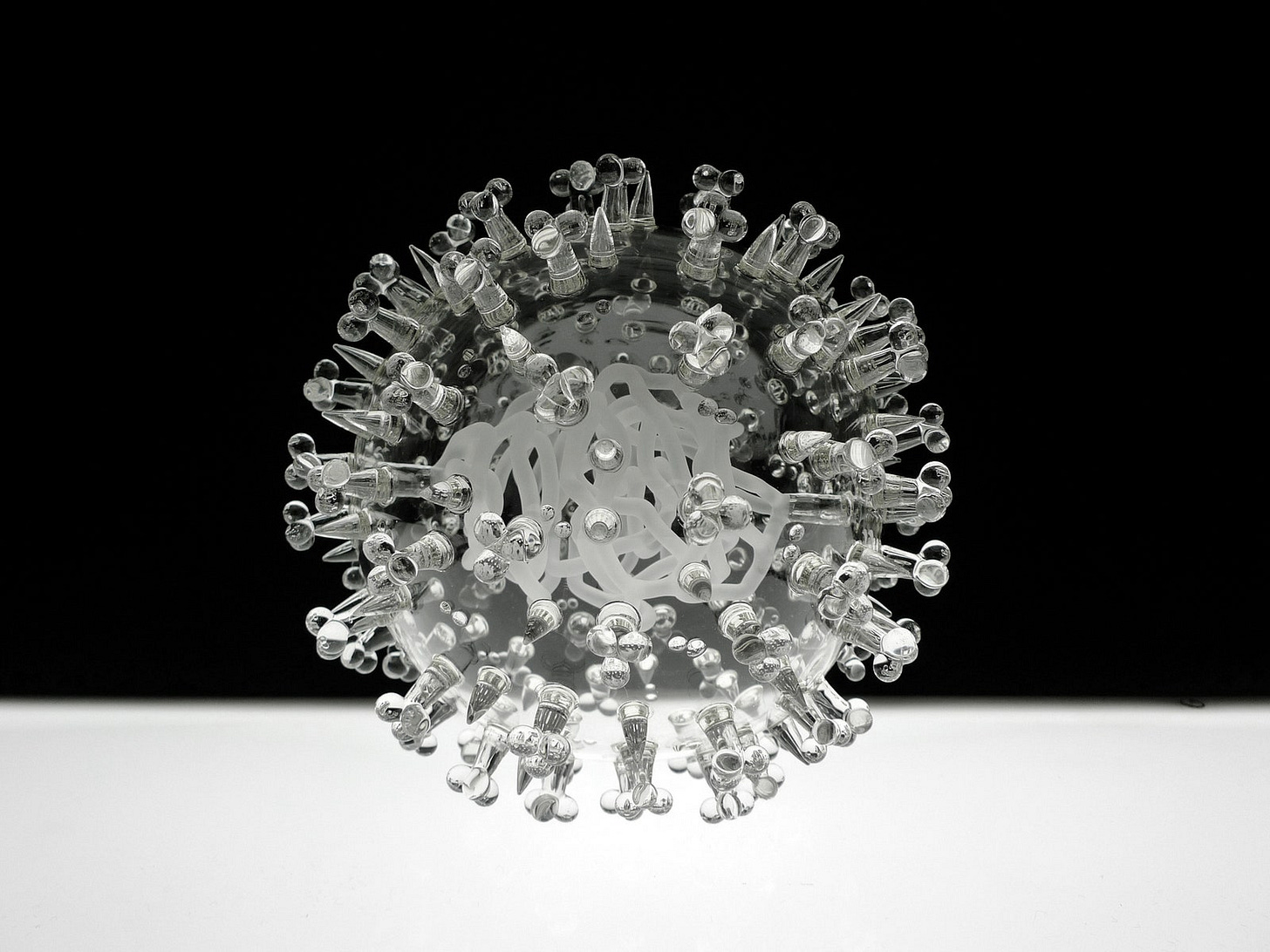

Colour-blind artist Luke Jerram’s glass sculpture of SARS Cov-2.

The artist is red-green colour-blind, and it bugged him when scientists added colour to make pictures of close-ups of viruses understandable. He started working with industrial glassblowers in northern England on more accurate representations of infectious agents like HIV, SARS-CoV, and Ebola. 'As science evolves, so do Jerram’s sculptures. Back when he made his first HIV model, people didn’t fully understand what the RNA looked like, but knowledge has improved, and Jerram is now on his third edition of the piece. A few years ago, he got a letter from a man suffering from the virus thanking him for revealing the enemy inside.’

“By making the invisible visible, we're able to feel like we have a better sense of control over it,” Jerram says. “Science can help give us a sense of empowerment.” The more representations we have, the better.’

Below a colourised artist’s impression of SARS Cov-2 produced by the CDC to highlight the spike proteins allegedly involved in pathogenicity so that the general public can better visualise the concept (and accept a spike protein jab).

Alissa Eckert the artist says ‘We wanted it to be really bold and attractive. First of all, we wouldn’t have wanted it to be too playful. People just wouldn’t take it seriously if we did that, right? We needed something that felt serious. So, we played upon the realism a little bit, using it to help people understand that this thing actually exists. That was my main goal, to make it pop out of the page. A little bit of drama and dramatic lighting to play with the emotions. That’s what I had in my head as I was designing.’

Technically the Ms are the most numerous proteins on the structure, but I tried doing that just to see, and it was too overwhelming and lost the focus. So, I downplayed the Ms, and focused on the S proteins, because they’re what really matters. The proteins are still accurate, but we’re focusing people’s attention differently.’

I was thinking about making a velvety texture on the proteins, and something that looked like you could touch it and feel it. And I also wanted it to be solid, a bit rocky, something found in nature. Because if you relate it to something that exists, it’s going to be more believable. The colours relate to the public health warning aspect, and the dramatic lighting, of course, the stark shadows.’

‘Herpes’

So much colour and funny spiky bits.

Below an electron micrograph, again from the CDC, of an object that’s so small it doesn’t interact with light and therefore has no colour. The sphere as well as the fringe of blobs could easily be artefacts of the EM process.

The object could be anything or nothing. Is it cellular or bacterial? There’s no way to know what it’s made of; let alone the ratio of proteins. It may have a function it may not. It’s certainly not shown that it’s causative of anything.

Scientists get carried away with technology and imagine things into being from what they see.

Artists then reimagine them into shapes and colourised images for us to be able to ‘visualise’. Artists emphasise the ‘important’ things with drama and ‘realism’- as though they really existed.

Eckert says ‘We’re working hard at being recognised. A lot of people don’t know what medical illustration is and why it’s important. There’s a whole network of medical illustrators out there working night and day on the Covid response and sharing materials to help each other out. Everybody’s hard at work.’

🐒